7 monkeys vs 2 people, not exactly a fair fight, is it?

For the past few months, my weekly calls with my dad have been peppered with tales of his latest escapades with a troop of monkeys in our backyard in Harare. Greystone Park, in Harare’s northern suburbs, is no stranger to encounters with the forces of nature. Having spent my entire life up until college here, I’ve witnessed my dad carefully coax cobras out of the house, furiously fumigate termite mounds in the garden and placate belligerent bees that had set up shop in an unassuming vase. Our house sits on the border of a vlei, leaving us more exposed to wildlife than our neighbours situated further inland. Monkeys aren’t newcomers to these parts; I remember occasionally running into them as a child, watching them jump effortlessly from one branch to another as they made their way across the vlei. Then, I could count the number of annual monkey sightings on one hand. Now, they were apparently daily customers of the vegetable gardens in the area – and don’t expect them to settle the bill, let alone leave a tip.

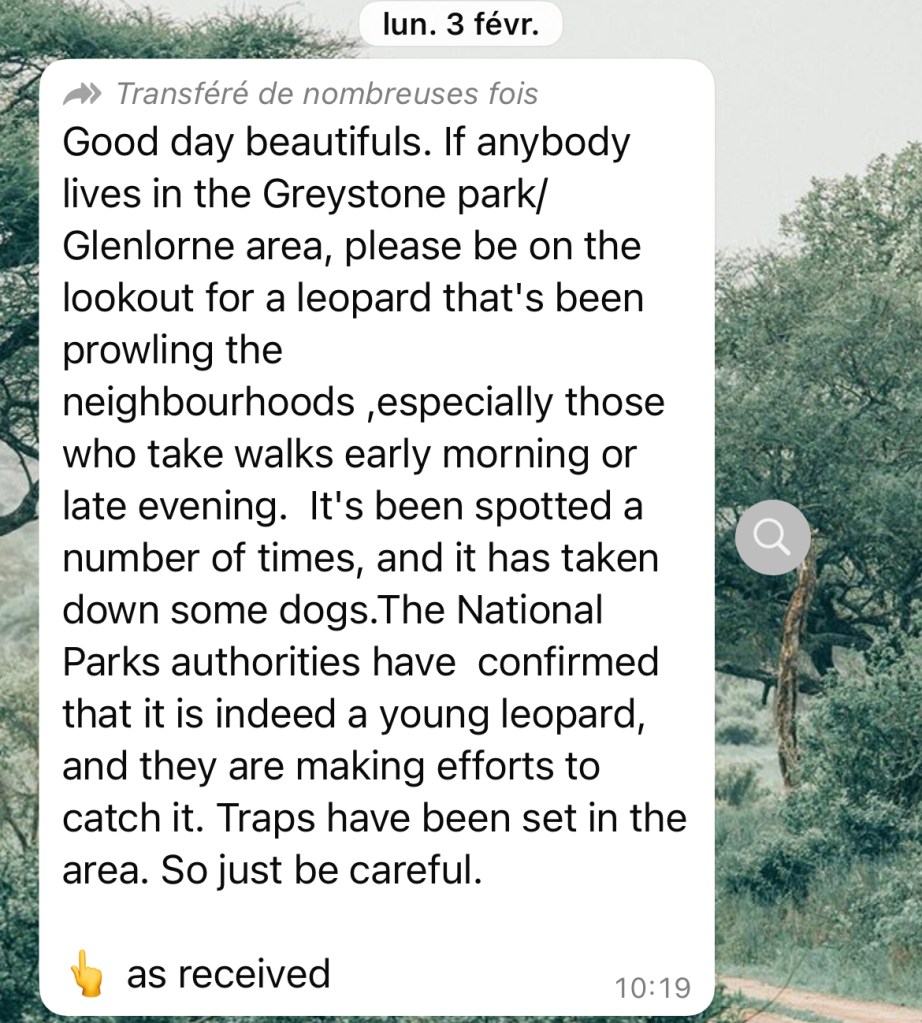

To add to the intrigue, our neighbours were also reporting sightings of a leopard prowling, supposedly in pursuit of its usual dinner. Sitting 12,500km away in the concrete jungle New York, I was taking these stories with a heavy dose of salt. Was I now supposed to believe our house had magically transformed into a national park?

Curiosity sufficiently aroused, I jetted back home to see what all the fuss was about. It didn’t take long after my arrival in Harare to see the trail of terror left behind. Discarded mealie husks and dung littered our garden and my dad pointed out with much disdain the monkey paw prints stamped on the walls of our house. Curiosity compounded, I waited with trepidation for my first encounter with the newest local vagrants.

It was whilst languishing in the sun that I had seen so little of in New York on my first day back that I had my first taste of battle. My attention drawn by the thundering aviary cry, ‘Khoh-khoh-khoh!’, of the purple-crested turaco, I scanned the trees hoping to catch a glimpse of one of my favourite birds. To my surprise, I found 2 birds sharing the shelter and food of a fruit tree with 2 monkeys; the birds not looking the least disturbed at all. Bewildered at the sight of peaceful kinship in the animal kingdom (often found lacking in today’s political environment), I watched on as the monkeys and birds feasted in harmony.

Up until this point, the monkeys seemed fairly innocuous. If all they were doing was munching on a few fruits and occasionally scuffing the odd wall then it didn’t seem like such a big deal to me. That was until a few moments later when a monkey emerged from our vegetable garden wielding a precious meal: a mealie. Mealies, known as corn in other parts of the world, are the staple food of Zimbabwe. Whether roasted over a fire and eaten whole or ground into mealiemeal to be cooked into sadza or porridge, mealies form a part of the daily diet of most Zimbabweans. Unfortunately, the monkeys can now call mealies their staple food too. Dashing across the garden, the delinquent monkey made its escape from our garden, the previously placid primates descended the fruit tree, hot in pursuit. Curiosity satisfied, I was convinced my dad had been exaggerating how much he was really battling the monkeys.

A few days pass without monkey sightings. Rumour has it Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Authority (Zimparks) culled an overpopulated troop of monkeys in Glen Lorne, just up the road from us. The neighbourhood group chat moves on from reporting the monkeys’ movements and I grow accustomed to the slow, quiet Harare lifestyle that is antithetical to New York living. That is, until my dad rouses me from my 2pm nap, ‘Come see, the monkeys are outside’. Lethargic, I drag myself into the garden and sure enough, we count 3 monkeys visibly nesting in the cypress trees on the western border of our garden. Sitting pretty about 15 metres above us, they have the best seats in the house. The sky heavy with clouds above us and the atmosphere thick with anticipation, we stare on in silence, waiting for them to make the first move.

Undeterred by our presence, the monkeys deftly descend the cypress trees as my dad steers himself ready for conflict with a home-fashioned slingshot, ‘The goal isn’t to hurt them, I just don’t want them getting comfortable here’, he asserts. Arming the slingshot with a pebble, my dad takes aim at a lone adult monkey just as it launches itself over the wall into our neighbour’s yard. A grating ‘Gra-gra-gra!’ erupts as the arrow-marked babblers nesting in their arboreal launchpad unleash a tirade of complaints. The birds relax as the thieving monkey vault back into our yard and reascends the cypress tree, one hand gripping tightly onto a mealie from our neighbour’s garden. My dad and I watch as one by one, the monkeys follow into the adjoining yard, dismissive of the litany of babblers’ cries and return victoriously with their prize. Triumphant, the monkeys taunt us from above as they dig in to their free lunch.

“We’ll be back”, my dad swears. Out of the slingshot’s range, we can only watch on as our unwanted guests settle comfortably in our trees. We retire to the veranda, awaiting the monkeys’ next move. A lone scout monkey rests at the tree’s canopy, his eyes on us and ours on him. I don’t mind waiting. With daily power cuts I lack the essential lifeline of the first world: internet access. In any case, this is infinitely more exciting than rewriting my resume, wrestling with my latest crochet project, or, dare I even say, polishing off another Poirot novel. What else is there to do? A lightbulb moment arrives and I crack open my fully charged laptop and begin writing this piece.

It seems the human residents aren’t the only ones unhappy with the primate settlers. As I’m writing on the veranda with the ever faithful scout watching me from his perch: a couple of crows attempt to dislodge him from the top of the tree. The scout nervously frees one hand to bat the large birds away but the circle around and dive towards the scout at full speed, sharp beaks aiming for blood. With all its energy focused on maintaining its tight grip on the tree, the scout, unsure of itself, once again tries to defend itself. Its fists find empty air as the crows artfully dodge its weak punts and they continue to taunt the lone monkey, “Caw! Caw!”. Eventually they grow bored of their jousting practice and fly off to find another poor soul to torture.

Eventually, the troop grows restless. ‘Ack! Ack! Ack!’, there is vicious hissing and scuffling as the monkeys scamper between the cypress trees bordering our yard and all we can observe from below is the thrashing of branches. A fight ensues high up in the trees which culminates in a monkey falling some 10 metres to the lowest branch on the tree, screeching all the way. It’s not just human vs monkey or bird vs monkey, this war is also being fought by monkeys against other monkeys. So much for the admiration for animal kinship that I had espoused earlier. ‘This is not a playground for monkeys’, my father announces emphatically. Ever determined, he reprises his so-called “weapon of mass destruction”, the slingshot, and sets out to dislodge the monkeys from the tree. The stage is officially set for battle.

We search high and low, far and wide for vantage points to strike from. Our house sits on three levels and we travel up the stairs to the uppermost balcony to meet the monkeys on equal ground, we circle around the garden below the tree canopies to catch them from below and we venture as far as our neighbour’s front yard to drive them away from us. However, they will not budge. Straddling the trees on the boundary between our property and the road, the monkeys are standing their ground. We can only watch despondently from the second floor balcony as they defiantly stay put. Across the street, what my brother and I call the ‘gardener’s conference’ has started to congregate as the gardeners from the area meet to talk stories. Completely unphased by our struggle, they casually look over and continue to trade neighbourhood gossip. Deterred but not resigned, we choose to temporarily pause our efforts. At 3pm I check my step count for the day: 1,637 steps taken/1.3km travelled. Bear in mind: I have not left the house today, this can all be attributed to monkey hunting. My dad opens a packet of biscuits, I brew a cup of tea and resume work on this article.

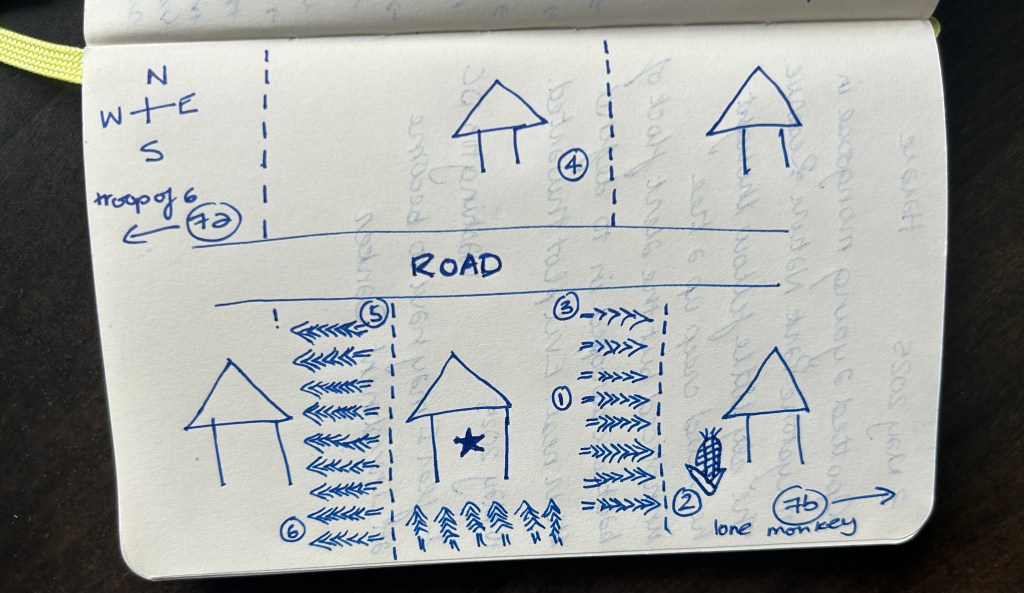

Halfway through my cuppa and not even 100 words in, my dad alerts me that he’s spotted the monkeys crossing the road. The gardener’s conference adjourned, the coast was clear for the monkeys to make their move. A small victory for us, at least they were no longer in our yard. We spy 4 of the monkeys sitting atop the jura wall directly across the street from us and instantly know that can’t be the whole troop. The quartet is looking desperately in our direction but not directly at us, they’re trying to coax the rest of the gang to cross the street to join them. All of a sudden, a familiar cow bell rings out loudly: it’s the ice-cream man. My dad and I watch as he wheels his way down the street, ringing a bell that brings joy to every child’s heart, looking for customers for his wares. Having devoured a Nutty Squirrel myself the previous day when it had been 5 degrees warmer, I wasn’t tempted to distract myself from the present situation with the rainclouds looming over us and the monkeys itching to find cover. With no takers, the ice-cream man moves on in search of sweet-toothed youths. The standoff resumes, 4 monkeys across the street, their compatriots in our front yard and us on the balcony, caught in-between.

It stays like this for a while. The quartet across the street grow impatient, ducking into the palm trees above, diving below the jura wall, dashing from left to right atop the wall but their friends won’t budge. 20 minutes later, they finally make a break for it. For the first time, we’re able to count the number of members of the troop: seven in total, two juveniles and five adults. They dash to the house opposite us, but just as we thought we were safe, the troop of seven quickly return across the street and climb into the trees of the adjoining house on the east side. It would only be a matter of time before they decided to pillage our vegetable garden.

Ever the enemies of their own progress, the guttural voices cry out as another fight erupts between 2 males. They dash from tree to tree, taking swipes at each other and both crash onto the ground on our side of the wall. One scampers up the tree, attempting to escape to our eastern neighbour, his opponent on his tail. They clash in an avocado tree and we watch helplessly from below as branches crash to the ground, indicating just how intense this battle is. Always an opportunist, my dad launches a pebble at the monkeys, hoping they’ll switch from attacking to retreating. The fight culminates with one monkey being thrown to the ground and it quickly withdraws west to the cypress trees where we first spotted them. The victor heads east, rejoining the troop in our neighbour’s leopard trees. My dad dashes in pursuit of the loser, the worst thing would be for this monkey to roost in our yard. It vaults itself quickly over the western wall and books it all the way across the maize field, far out of sight and reach. The monkey is sure not to return I comment, ‘It’s being pursued by 2 different people’. My dad adds ‘2 different motives but 1 common goal: nobody wants it around’.

It’s just before 4pm, the sky so dark with heavy cloud cover that the garden lights illuminate as electricity returns. Eager to rejoin my internet friends who have surely missed me, I check my phone as a string of notifications pours in. My dad reminds me that the job’s not finished: we have to make sure the rest of the troop also moves on. We climb back up to the second floor balcony just to see the monkeys dashing through the leopard trees, being hotly pursued by the 2 primary school aged boys next door who are hooting and hollering at the primates making screeches indistinguishable from their own. Their methods seemingly more effective than ours, we count six monkeys descending back onto the road at top speed, making their way further west up the street. Challenge accepted, the boys eagerly mount their bikes and beg their mum to let them chase the monkeys down. Shot down, the boys retire as the monkeys continue their search for a roost. One thing’s for sure: it won’t be anywhere close to us.

Somewhere in the neighbourhood, the lone vagabond monkey licks its wounds and rests to be ready to fight another day. What it doesn’t know is that we will also be ready.